This fairy tale is really long so I’m going to split the blog into 2 parts.

Brief History: Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev also collected this story, which starts off in a way similiar to so many western fairy tales. Vasilisa’s mother dies and leaves her a wooden doll which if she feeds and gives drinks to will help her. I’m not sure if the doll feeding was a like a Betsy-Wetsy situation or like a Golem or more like when a little kid holds food up to a toy’s closed mouth. Either way, the doll is clearly magic. . . creepy, creepy magic. This, of course, comes in handy when dad remarries and allows the new wife and step-daughters to treat Vasilisa terribly. In true Cinderella fashion, step-mommy dearest gives Vasilisa impossible tasks which the doll helps her with. Years pass like this and Vasilisa can’t get a date because no one wants to marry her step-sister, so she is also trapped in that life (remember, can’t leave home unless married in this time period).

One day, her step-sister breaks a rule and extinguishes all fire in the house. She sends Vasilisa out to get a light before the parents come home (they don’t have matches, I guess?) and this leads our hero to a hut on chicken feet surrounded by a fence of human bones. The door has hinges made of human hands. The locks were made of human jaw bones. This witch doesn’t waste any part of her kills. You have to give her credit for that.

In case you haven’t guess - it’s Baba Yaga in her flying mortar time! Vasilia tries to hide but Baba Yaga sniffs her out and asks if she was sent. When the young woman explains that her step-sister sent her, Baba Yaga ominously replies, “I know her and she’ll know me.” The witch keeps Vasilisa as a slave, telling her she will give her fire if she completes all o the impossible tasks. Once again, the doll helps her. Not every good decision she makes is based upon her imaginary friend. Vasilisa has her own subtle smarts to keep herself alive. She tries to escape every chance she gets, using the same spells as Baba Yaga. Another example, the witch dares her to ask questions. She chooses to ask about the red, white, and black riders she sees going by the chicken feet hut at various times of day over asking about anything personal related to Baba Yaga (like why does she have animated disembodied hands or need poppy seeds).

When day pass and the exhausted Vasilisa completes every disgusting and difficult task she’s given, a frustrated Baba Yaga asks how she’s managed to do this. In true Baba Yaga fashion, she was looking forward to killing the young woman when she failed. Vasilisa doesn’t lie, but also doesn’t say outright that she has an enchanted doll in her pocket. Her response is “with my mother’s blessing”. This answer grossed out Baba Yaga, who thinks sentiment and blessings are icky, so she cast Vasilisa from her house and gave her the fire she’d come for. This fire was placed within a skull turned lantern (admit it, sounds like a boss Halloween decoration).

Vasilisa finally goes back home where her step-mother and step-sister have been cursed with darkness (no candles could be lit and fires would instantly extinguish). Imagine their happiness when Vasilisa brings home the skull lantern. . . which then burns them both to ashes. Witch fire. What are you going to do, right? Handle with care. After burying the skull, Vasilisa runs away, becomes a weavers apprentice, and weave a cloth so beautiful she marries the Tsar.

Analysis: Vasilisa the Beautiful has also been titled the Brave and the Wise because of her calm, leveled head. In some versions, she doesn’t marry the Tsar, instead living happily with her father and looking forward to a brighter future. Get it? Brighter? Because she brought home fire? Okay fine. To start, the fire thing is a pretty big theme in Russian folklore. It’s like it’s freezing cold there or something. Being saved by the blessing of her mother is where old Slavic folklore and the contemporary Russian Christianity meet. A witch of the ancient world would not being able to stomach prayers from the monotheoist religion. This theme is pretty common in Eastern European stories.

The name Vasilisa and her titles of wise and fair and brave accompany other stories as well. One where she tricks a Tsar into believing she’s a brave soldier. One where she outsmarts a sea king. One where she enlists the help of a prince to end her curse of being turned into a frog in daylight hours (in that one Baba Yaga is helpful). The point is that name goes hand-in-hand with tales of women who are trying to save themselves or ask for help needed.

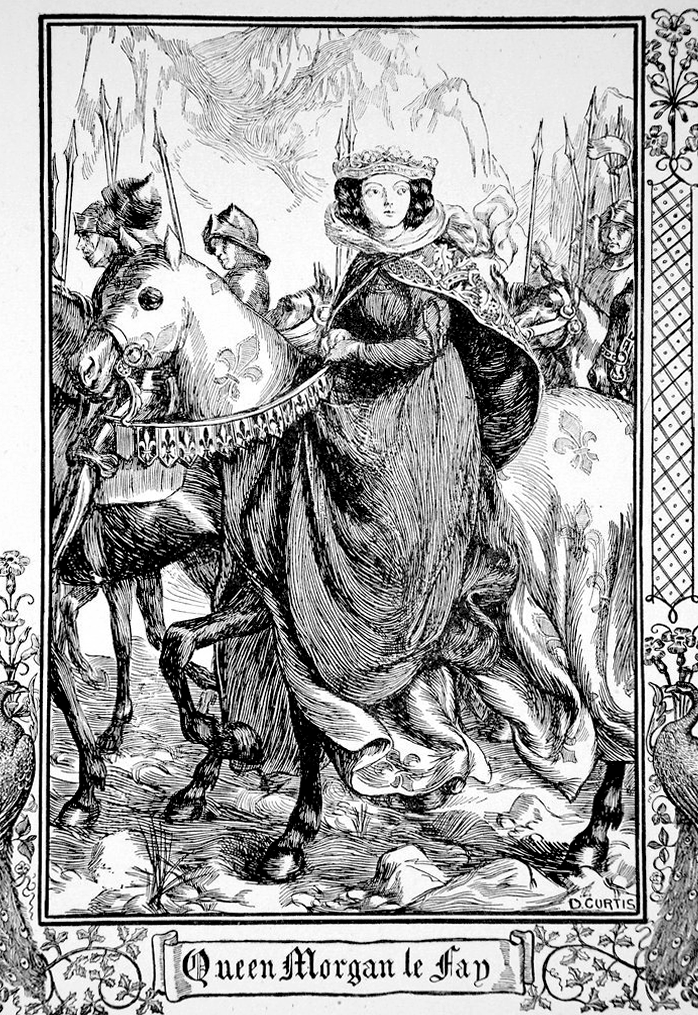

By the way, it turns out the riders are the personification of day, sunshine, and night. This is never really made important to story other than showing the measure of time and the suggestion that Baba Yaga somehow controls the day and night, but illustrators love the imagery and the riders are usually in every picture book version of the story.

To be continued next week.